Map of Sierra Nevada

Half Dome Region

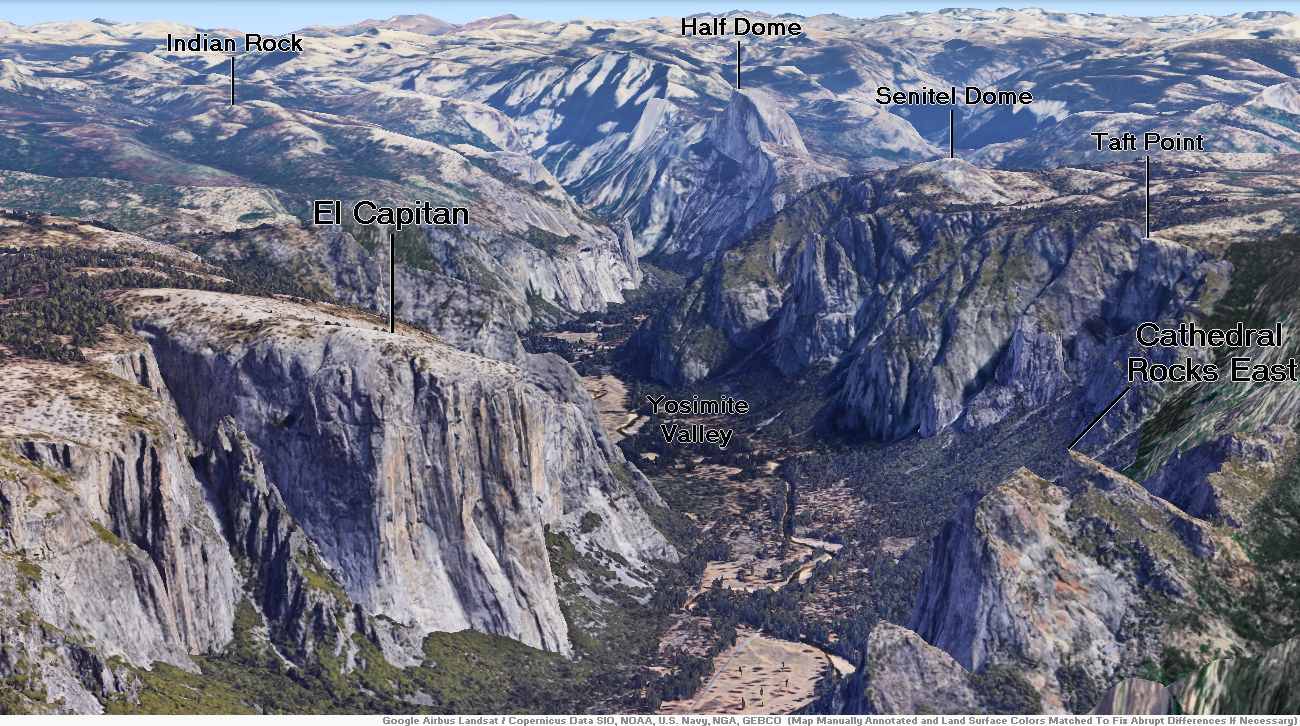

Half Dome Panoramic

Half Dome is a quartz monzonite batholith at the eastern end of Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park, California. It is a well-known rock formation in the park, named for its distinct shape. One side is a sheer face while the other three sides are smooth and round, making it appear like a dome cut in half. It stands at nearly 8,800 feet above sea level and is composed of quartz monzonite, an igneous rock that solidified several thousand feet within the Earth. At its core are the remains of a magma chamber that cooled slowly and crystallized beneath the Earth’s surface. The solidified magma chamber was then exposed and cut in half by erosion, therefore leading to the geographic name Half Dome.[3]

Geology

Main article: Geology of the Yosemite area

The impression from the valley floor that this is a round dome that has lost its northwest half, is just an illusion. From Washburn Point, Half Dome can be seen as a thin ridge of rock, an arête, that is oriented northeast–southwest, with its southeast side almost as steep as its northwest side except for the very top. Although the trend of this ridge, as well as that of Tenaya Canyon, is probably controlled by master joints, 80 percent of the northwest “half” of the original dome may well still be there.

Ascents

As late as the 1870s, Half Dome was described as “perfectly inaccessible” by Josiah Whitney of the California Geological Survey.[4] The summit was reached by George G. Anderson in October 1875, via a route constructed by drilling and placing iron eye bolts into the smooth rock.[5] Anderson had previously tried a variety of methods, including using pitch from nearby pine trees for extra friction.[6]

Anderson subsequently went on to add ropes to his eye bolts, so that other people could climb. Among those who took advantage was the first woman to climb Half Dome in 1876, S. L. Dutcher, of San Francisco. In 1877 James Mason Hutchings along with Anderson led a climb which included Hutchings’ daughter Cosie, his son Willie, his mother-in-law Florence Sproat, aged 65, and two other women.[6][7]

Today, Half Dome may be ascended in several different ways. Thousands of hikers reach the top each year by following an 8.5 mi (13.7 km) trail from the valley floor. After a rigorous 2 mi (3.2 km) approach, including several hundred feet of rock stairs, the final pitch up the peak’s steep but somewhat rounded east face is ascended with the aid of a pair of post-mounted steel cables originally constructed close to the Anderson route in 1919.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Half Dome, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

El Capitan Panoramic

PdaMai (iStock)

El Capitan (Spanish: El Capitán; lit. ’the Captain’ or ‘the Chief’) is a vertical rock formation in Yosemite National Park, on the north side of Yosemite Valley, near its western end. The granite monolith is about 3,000 feet (914 m) from base to summit along its tallest face and is a world-famous location for big wall climbing, including the disciplines of aid climbing, free climbing, and more recently for free solo climbing.

Naming

The formation was named “El Capitan” by the Mariposa Battalion when they explored the valley in 1851. El Capitán (“the captain”, “the chief”) was taken to be a loose Spanish translation of the local Native American name for the cliff, “Tutokanula” or “Rock Chief” (the exact spelling of Tutokanula varies in different accounts as it is a phonetic transcription from the Miwok language).[4]

The “Rock Chief” etymology is based on the written account of Mariposa Battalion doctor Lafayette Bunnell in his 1892 book.[5] Bunnell reports that Ahwahneechee Chief Tenaya explained to him, forty-one years earlier, in 1851, that the massive formation, called Tutokanula, could be translated as “Rock Chief” because the face of the cliff looks like a giant rock Chief. In Bunnell’s account, however, he notes that this translation may be wrong, stating: “I am not etymologist enough to understand just how the word has been constructed… [If] I am found in error, I shall be most willing to acknowledge it, for few things appear more uncertain, or more difficult to obtain, than a complete understanding of the soul of an Indian language.” [5]

An alternative etymology is that “Tutokanula” is Miwok for “Inchworm Rock”.[6] Julia F. Parker, the preeminent Coast Miwok-Kashaya Pomo basket-weaver and Yosemite Museum cultural ambassador since 1960, explains that the name Tutokanula, or “Inchworm Rock”, originates in the Miwok creation story for the giant rock, a legend in which two bear cubs are improbably rescued by a humble inchworm. In the story, a mother bear and her two cubs are walking along the river. The mother forages for seeds and berries while the two cubs nap in the sun on a flat rock. While the cubs sleep, the rock grows and grows, above the trees and into the sky. The mother bear is unable to climb the rock to get to her cubs and she becomes afraid and asks for help. The fox, the mouse, the mountain lion, and every other animal tries to climb to the top of the giant rock but they each fail. Finally, the lowly little inchworm tries the climb and successfully makes it all the way to the top and rescues the cubs. All the animals are happy to see that the little inchworm has saved the two bear cubs and the rock is named in the inchworm’s honor.[7]

The “Inchworm Rock” version of the meaning of Tutokanula is also described in the story “Two Bear Cubs: A Miwok Legend from California’s Yosemite Valley” by Robert D. San Souci[8] and in the First People Miwok recounting of the El Cap legend.[9]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article El Capitan, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Cathedral Peak is part of the Cathedral Range, a mountain range in the south-central portion of Yosemite National Park in eastern Mariposa and Tuolumne Counties. The range is an offshoot of the Sierra Nevada. The peak which lends its name to the range derives its name from its cathedral-shaped peak, which was formed by glacial activity: the peak remained uneroded above the glaciers in the Pleistocene.

Geography

Cathedral Peak has a subsidiary summit to the west called Eichorn Pinnacle, for Jules Eichorn, who first ascended a class 5.4 route to its summit on July 24, 1931, with Glen Dawson.

In 1869, John Muir wrote in My first summer in the Sierra:

The body of the Cathedral is nearly square, and the roof slopes are wonderfully regular and symmetrical, the ridge trending northeast and southwest. This direction has apparently been determined by structure joints in the granite. The gable on the northeast end is magnificent in size and simplicity, and at its base there is a big snow-bank protected by the shadow of the building. The front is adorned with many pinnacles and a tall spire of curious workmanship. Here too the joints in the rock are seen to have played an important part in determining their forms and size and general arrangement. The Cathedral is said to be about eleven thousand feet above the sea, but the height of the building itself above the level of the ridge it stands on is about fifteen hundred feet. A mile or so to the westward there is a handsome lake, and the glacier-polished granite about it is shining so brightly it is not easy in some places to trace the line between the rock and water, both shining alike.[5]

Geology

The Cathedral Peak Granodiorite of Cathedral Peak is an intrusion into an area of older intrusive (or plutonic) and metamorphic rock in the Sierra Nevada Batholith. It is part of a grouping of intrusions called the Tuolumne Intrusive Suite. Cathedral Peak is the youngest of the rock formations in the Suite, dating to the Cretaceous Period at 83 million years ago. Its composition is mainly granodiorite with phenocrysts of microcline.[6]

Cathedral Peak was a nunatak during the Tioga glaciation of the last ice age, the peak projected above the glaciers, which carved and sharpened the peak’s base while plucking away at its sides.[7][8][9][10]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Cathedral Peak (California), which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Mount Whitney Region

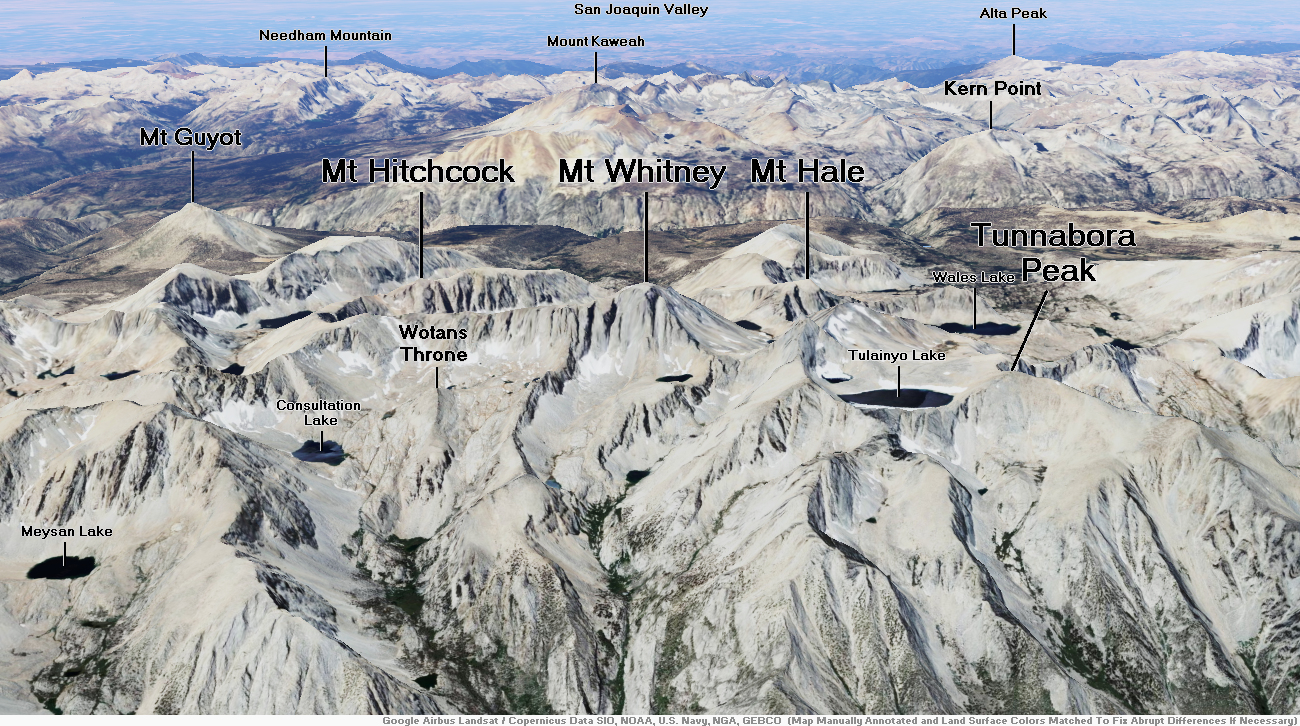

Mount Whitney Panoramic

Mount Whitney (Paiute: Too-man-i-goo-yah[8] or Too-man-go-yah[9]) is the highest mountain in the contiguous United States, with an elevation of 14,505 feet (4,421 m).[1] It is in East–Central California, in the Sierra Nevada, on the boundary between California’s Inyo and Tulare counties, and 84.6 miles (136.2 km)[10] west-northwest of North America’s lowest topographic point, Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park, at 282 ft (86 m) below sea level.[11] The mountain’s west slope is in Sequoia National Park and the summit is the southern terminus of the John Muir Trail, which runs 211.9 mi (341.0 km) from Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley.[12] The eastern slopes are in Inyo National Forest in Inyo County. Mount Whitney is ranked 18th by topographic isolation.

Geography

Mount Whitney’s summit is on the Sierra Crest and the Great Basin Divide. It lies near many of the Sierra Nevada‘s highest peaks.[13] The peak rises dramatically above the Owens Valley, sitting 10,778 feet (3,285 m) or just over 2 mi (3.2 km) above the town of Lone Pine 15 mi (24 km) to the east, in the Owens Valley.[13] It rises more gradually on the west side, lying only about 3,000 feet (914 m) above the John Muir Trail at Guitar Lake.[14]

The mountain is partially dome-shaped, with its famously jagged ridges extending to the sides.[15] Mount Whitney is above the tree line and has an alpine climate and ecology.[16] Very few plants grow near the summit: one example is the sky pilot, a cushion plant that grows low to the ground.[17] The only animals are transient, such as the butterfly Parnassius phoebus and the gray-crowned rosy finch.[17]

Hydrology

The mountain is the highest point on the Great Basin Divide. Waterways on the peak’s west side flow into Whitney Creek, which flows into the Kern River. The Kern River terminates at Bakersfield in the Tulare Basin, the southern part of the San Joaquin Valley. Today, the water in the Tulare Basin is largely diverted for agriculture. Historically, during very wet years, water overflowed from the Tulare Basin into the San Joaquin River, which flows to the Pacific Ocean.

From the east, water from Mount Whitney flows to Lone Pine Creek, where most of the water is diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct via a sluice. Some water in the creek is allowed to continue on its natural course, joining the Owens River, which terminates at Owens Lake, an endorheic lake of the Great Basin.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Whitney, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Mount Tallac Region

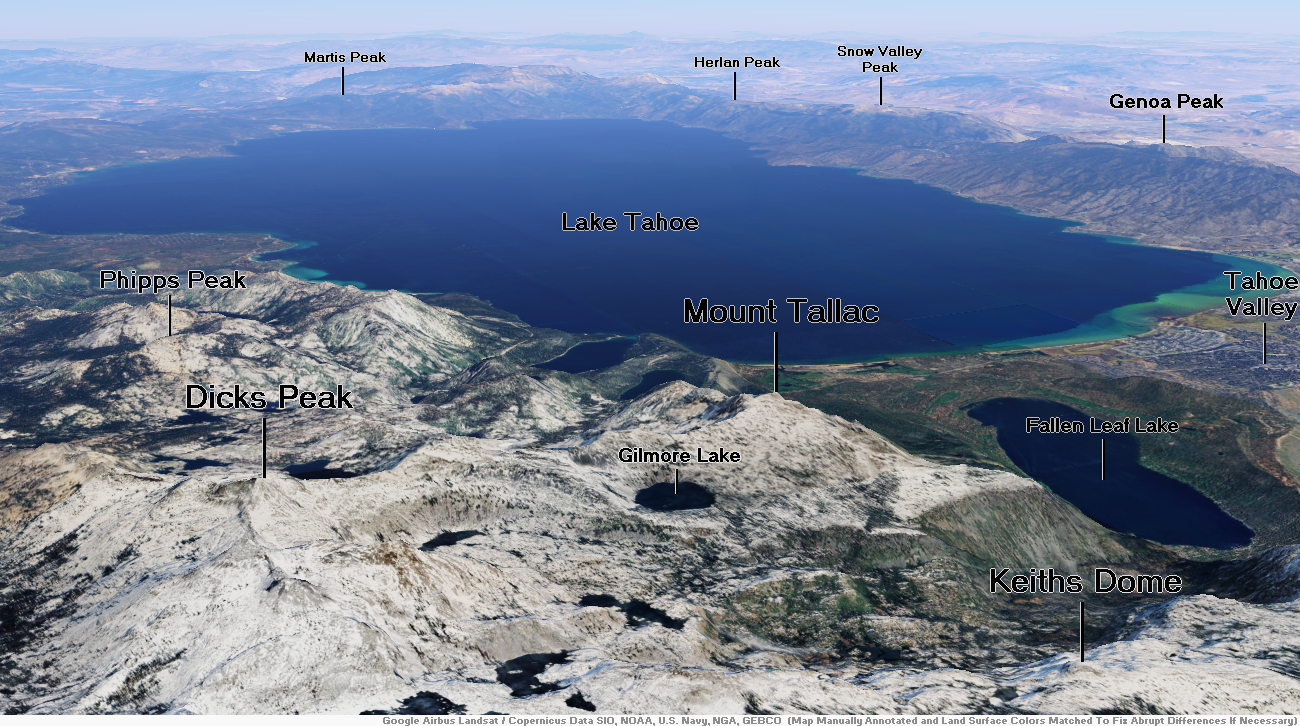

![]()

Mount Tallac is a mountain peak southwest of Lake Tahoe, in El Dorado County, California. The peak lies within the Desolation Wilderness in the Eldorado National Forest. It is quite visible from State Routes 89 and 28, and U.S. Route 50. A “cross of snow” is clearly visible on the mountain’s face during the winter, spring, and early summer months.

The Aetherius Society considers it to be one of its 19 holy mountains.[7][8][9]

History

The mountain is shown on maps of the Whitney Survey as Chrystal Peak. In 1877, the Wheeler Survey named the peak “Tallac”, after the Washo word “daláʔak”, meaning ‘big mountain’.[10]

Access

An estimated 10,000 climb the peak each year via routes approaching the summit from Desolation Wilderness to the west, Fallen Leaf Lake to the East, and access roads from the north.[11] Wilderness permits are required to hike Mount Tallac. For day hikes, permits are free and self-issued at the trailhead.[12] There is a quota for overnight hikes on Mount Tallac (and throughout Desolation Wilderness), but there is no quota for day hiking.

Climate

Mount Tallac is located in an alpine climate zone.[13] Most weather fronts originate in the Pacific Ocean, and travel east toward the Sierra Nevada mountains. As fronts approach, they are forced upward by the peaks (orographic lift), causing them to drop their moisture in the form of rain or snowfall onto the range.

In popular culture

The opening sequence of the TV series Bonanza was filmed at the McFaul Creek Meadow, with Mount Tallac in the background.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Tallac, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).