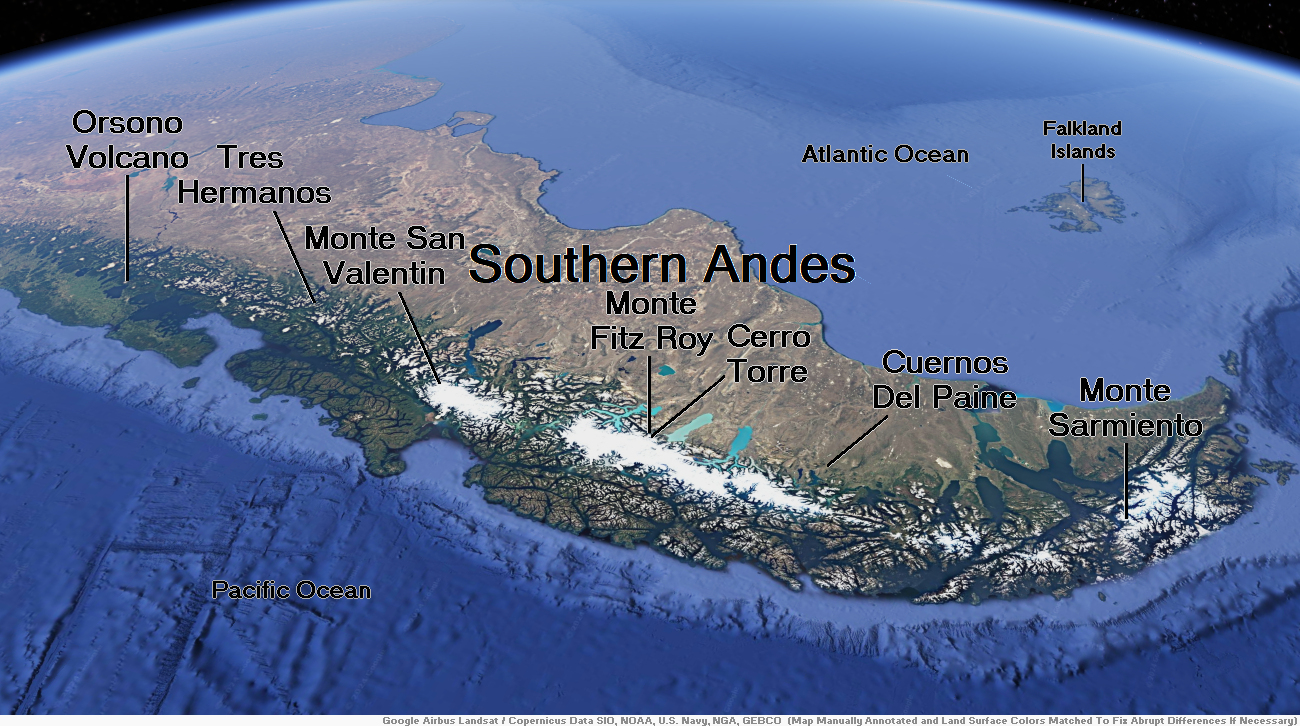

Map of Southern Andes

Fitz Roy Region 1

Fitz Roy Region 2

Fitz Roy Panoramic

EyeEm Mobile GmbH (iStock)

![]()

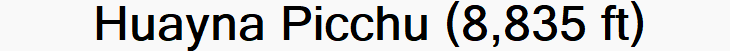

Monte Fitz Roy (also known as Cerro Chaltén, Cerro Fitz Roy, or simply Mount Fitz Roy) is a mountain in Patagonia, on the border between Argentina and Chile.[2][3][6][4][5] It is located in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, near El Chaltén village and Viedma Lake. It was first climbed in 1952 by French alpinists Lionel Terray and Guido Magnone.

The first Europeans recorded as seeing Mount Fitz Roy were the Spanish explorer Antonio de Viedma and his companions, who reached the shores of Viedma Lake in 1783. Argentine explorer Francisco Moreno saw the mountain on 2 March 1877; he named it Fitz Roy in honour of Robert FitzRoy who, as captain of HMS Beagle, had travelled up the Santa Cruz River in 1834 and charted large parts of the Patagonian coast.[7]

Cerro is a Spanish word meaning ridge or hill, while Chaltén comes from a Tehuelche (Aonikenk) word meaning “smoking mountain”, because a cloud usually forms around the mountain’s peak. Fitz Roy is one of several peaks the Tehuelche called Chaltén.[7]

Geography

Argentina and Chile have agreed that their international border detours eastwards to pass over the main summit,[2] but a large part of the border to the south of the summit, as far as Cerro Murallón, remains undefined.[8] The mountain is the symbol of the Argentine Santa Cruz Province, which includes its representation on its flag and its coat of arms.

On February 27, 2014, Chile’s National Forestry Corporation created the Chaltén Mountain Range Natural Site by Resolution No. 74, which covers the Chilean side of Mount Fitz Roy and the surrounding mountain range.[9]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Fitz Roy, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

Cerro Torre is one of the mountains of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field in South America. It is located on the border dividing Argentina and Chile,[3] west of Fitz Roy (also known as Cerro Chaltén). At 3,128 m (10,262 ft), the peak is the highest of a four mountain chain: the other peaks are Torre Egger (2,685 m (8,809 ft)),[4] Punta Herron, and Cerro Standhardt. The top of the mountain often has a mushroom of rime ice, formed by the constant strong winds, increasing the difficulty of reaching the actual summit.

First ascent

Cesare Maestri claimed in 1959 that he and Toni Egger had reached the summit and that Egger had been swept to his death by an avalanche while they were descending. Maestri declared that Egger had the camera with the pictures of the summit, but this camera was never found. Inconsistencies in Maestri’s account, and the lack of bolts, pitons or fixed ropes on the route, have led most mountaineers to doubt Maestri’s claim.[5][6] In 2005, Ermanno Salvaterra, Rolando Garibotti and Alessandro Beltrami, after many attempts by world-class alpinists, put up a confirmed route on the face that Maestri claimed to have climbed.[7][8] They did not find any evidence of previous climbing on the route described by Maestri and found the route significantly different from Maestri’s description.

Maestri went back to Cerro Torre in 1970 with Ezio Alimonta, Daniele Angeli, Claudio Baldessarri, Carlo Claus and Pietro Vidi, trying a new route on the southeast face. With the aid of a gas-powered compressor drill, Maestri equipped 350 metres (1,150 ft) of rock with bolts and got to the end of the rocky part of the mountain, just below the ice mushroom.[9] Maestri claimed that “the mushroom is not part of the mountain” and did not continue to the summit. The compressor was left, tied to the last bolts, 100 m (330 ft) below the top. Maestri was heavily criticized for the “unfair” methods he used to climb the mountain.[10]

The route Maestri followed is now known as the Compressor route and was climbed to the summit in 1979 by Jim Bridwell and Steve Brewer.[6][11] Most parties consider the ascent complete only if they summit the often-difficult ice-rime mushroom.[citation needed]

The first undisputed ascent was made in 1974 by the “Ragni di Lecco” climbers Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari, and Pino Negri.[7] The controversies regarding Maestri’s claims are the focus of the 2014 book on Cerro Torre, The Tower, by Kelly Cordes.[12]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Cerro Torre, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

Osorno Volcano is a 2,652-metre-tall (8,701 ft) conical stratovolcano lying between Osorno Province and Llanquihue Province in the Los Lagos Region of southern Chile. It stands on the southeastern shore of Llanquihue Lake, and also towers over Todos los Santos Lake. Osorno is considered a symbol of the local landscape and, as such, tends to be the referential element of the area in regards to tourism. By some definitions, it marks the northern boundary of Chilean Patagonia.

Etymology

The volcano’s current name comes from the nearby city of Osorno, from which it was visible to Spanish settlers. Native populations gave it different names, such as Purailla, Purarhue, Prarauque, Peripillan, Choshueco, Hueñauca, and Guanauca. The latter two were the most commonly used names in the mid-18th century.[2][3]

Overview

The volcano has a height of 2,652 meters (8,701 feet) and an imposing conical shape which looms over Lago Llanquihue. It is situated across the lake from the cities of Frutillar, Puerto Varas, and Llanquehue. It dominates the region’s landscape, and its height means that it can be seen from the entire province of Osorno, even in some places on the island of Chiloé. Volcán Osorno is located almost 45 kilometers (28 miles) northeast of Puerto Varas. Though in geological terms it is still considered an active volcano, there has been no volcanic activity in over one hundred years, it having last erupted in 1869. In recent years the volcano has become a popular tourist attraction. Skiing and hiking have become common recreational activities on the mountain.[4]

The volcano is accessible from the towns of Puerto Klocker, Ensenada, and Petrohué, and at its base is the town of Las Cascadas.

Volcanic activity

Volcán Osorno is one of the most active volcanoes of the southern Chilean Andes, with eleven eruptions recorded between 1575 and 1869. It sits on top of a 250,000-year-old eroded stratovolcano, La Picada, with a 6-km-wide caldera.[5][6]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Orsorno (volcano), which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Map of Central Andes

Aconcagua Region

![]()

Aconcagua (Spanish pronunciation: [akoŋˈkaɣwa]) is a mountain in the Principal Cordillera[4] of the Andes mountain range, in Mendoza Province, Argentina. It is the highest mountain in the Americas, the highest outside Asia,[5] and the highest in both the Western Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere[1] with a summit elevation of 6,961 metres (22,838 ft). Despite its size and stature, it is only the 189th highest mountain in the world.[6] It lies 112 kilometres (70 miles) northwest of the provincial capital, the city of Mendoza, about five kilometres (three miles) from San Juan Province, and 15 km (9 mi) from Argentina’s border with Chile.[7] The mountain is one of the Seven Summits, the highest peaks on each of the seven continents.

Aconcagua is bounded by the Valle de las Vacas to the north and east and the Valle de los Horcones Inferior to the west and south. The mountain and its surroundings are part of Aconcagua Provincial Park. The mountain has a number of glaciers. The largest glacier is the Ventisquero Horcones Inferior at about 10 km (6 mi) long, which descends from the south face to about 3,600 m (11,800 ft) in elevation near the Confluencia camp.[8] Two other large glacier systems are the Ventisquero de las Vacas Sur and Glaciar Este/Ventisquero Relinchos system at about 5 km (3 mi) long. The best known is the northeastern or Polish Glacier, as it is a common route of ascent.

Etymology

The origin of the name is uncertain. It may be from the Mapudungun Aconca-Hue, which refers to the Aconcagua River and means “comes from the other side”;[7] the Quechua Ackon Cahuak, meaning “Sentinel of Stone”;[9] the Quechua Anco Cahuac, meaning “White Sentinel”;[3] or the Aymara Janq’u Q’awa, meaning “White Ravine”.[10]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Aconcagua, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

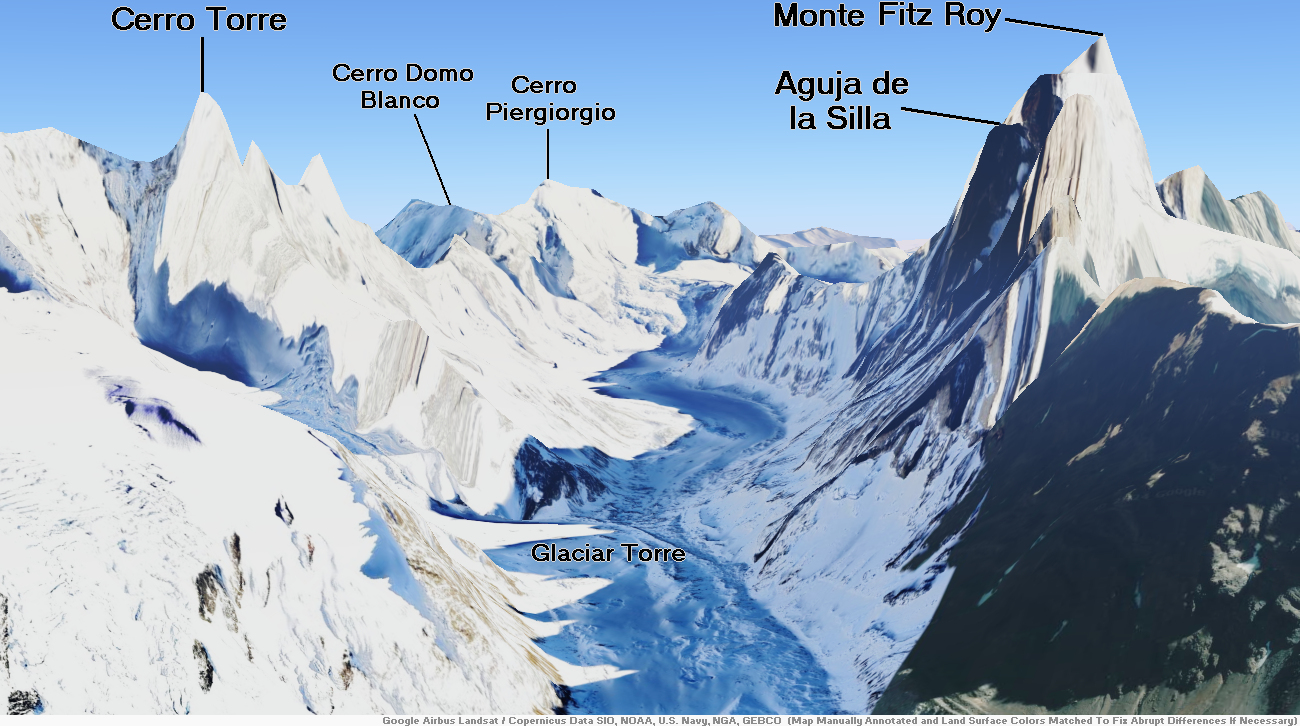

Licancabur Region

![]()

Licancabur (Spanish pronunciation: [likaŋkaˈβuɾ]) is a prominent, 5,916-metre-high (19,409 ft) stratovolcano on the Bolivia–Chile border in the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes. It is capped by a 400–500-metre (1,300–1,600 ft) wide summit crater; it contains Licancabur Lake, a crater lake that is among the highest lakes in the world. There are no glaciers owing to the arid climate. Numerous animal species and plants live on the mountain. The volcanoes Sairecabur and Juriques are north and east of Licancabur, respectively.

Licancabur formed on top of ignimbrites produced by other volcanoes and it has been active during the Holocene. Three stages of lava flows emanated from the edifice and have a young appearance. Although no historical eruptions of the volcano are known, lava flows extending into Laguna Verde have been dated to 13,240 ± 100 Before Present and there may be residual heat in the mountain. The volcano has primarily erupted andesite, with small amounts of dacite and basaltic andesite.

Several archaeological sites have been found on the mountain, both on its summit and northeastern foot. They are thought to have been constructed by the Inca or Atacama people for religious and cultural ceremonies and are among the most important in the region. The mountain is the subject of a number of myths, in which it is viewed as the husband of another mountain, a hiding place used by the Inca, or the burial of an Inca king.

Etymology and importance

The name Licancabur comes from the Kunza language,[2] in which lican means “people” or “town” and cábur/[3] caur, caure or cauri mean “mountain”.[4] The name may refer to the archaeological sites on the mountain.[5] The name of the volcano has also been translated as “upper village”.[6] Other names are Licancáguar,[3] Licancaur,[5] Tata Likanku[7] and Volcán de Atacama.[8]

Licancabur is one of the widely known volcanoes within Bolivia and Chile[b] and can be seen from San Pedro de Atacama.[10][11] The region was conquered by the Inca in the 14th century and by the Spanish during the 16th century.[2] Today it is of interest for research on animal health, remote sensing, telecommunication and the fact that the environment around Licancabur may be the closest equivalent to Mars that exists on Earth,[12][13][14] while current conditions at its lakes resemble those of former lakes on Mars.[15][16][12]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Licancabur, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Illimani Panoramic

Illimani Panoramic

Roger Villavicencio

![]()

Illimani (Aymara and Spanish pronunciation: [iʎiˈmani]) is the highest mountain in the Cordillera Real (part of the Cordillera Oriental, a subrange of the Andes) of western Bolivia. It lies near the cities of El Alto and La Paz at the eastern edge of the Altiplano. It is the second highest peak in Bolivia, after Nevado Sajama, and the eighteenth highest peak in South America.[3] The snow line lies at about 4,570 metres (15,000 ft) above sea level, and glaciers are found on the northern face at 4,982 m (16,350 ft). The mountain has four main peaks; the highest is the south summit, Nevado Illimani, which is a popular ascent for mountain climbers.

Geologically, Illimani is composed primarily of granodiorite, intruded during the Cenozoic era into the sedimentary rock, which forms the bulk of the Cordillera Real.[4]

Illimani is quite visible from the cities of El Alto and La Paz, and is their major landmark. The mountain has been the subject of many local songs, most importantly “Illimani”, with the following refrain: “¡Illimani, Illimani, centinela tú eres de La Paz! ¡Illimani, Illimani, perla andina eres de Bolivia!” (“Illimani, Illimani, you are the sentinel of La Paz! Illimani, Illimani, you are Bolivia’s andean pearl!”)

Climbing

Illimani was first attempted in 1877 by the French explorator Charles Wiener, J. de Grumkow, and J. C. Ocampo. They failed to reach the main summit, but did reach a southeastern subsummit, on 19 May 1877, Wiener named it the “Pic de Paris”, and left a French flag on top of it.[5] In 1898, British climber William Martin Conway and two Italian guides, J.A. Maquignaz and L. Pellissier, made the first recorded ascent of the peak, again from the southeast. (They found a piece of Aymara rope at over 6,000 m (20,000 ft), so an earlier ascent cannot be completely discounted[6]).

The current standard route on the mountain climbs the west ridge of the main summit. It was first climbed in 1940, by the Germans R. Boetcher, F. Fritz, and W. Kühn, and is graded French PD+/AD-.[6] This route usually requires four days, the summit being reached in the morning of the third day.

In July 2010 German climber Florian Hill and long-time Bolivian resident Robert Rauch climbed a new route on the ‘South Face’, completing most of the 1700m of ascent in 21 hours. Deliver Me (WI 6 and M6+) appears to climb the gable-end of the South West Ridge, a very steep wall threatened by large broken seracs.[7]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Illimani, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

Huayna Potosí is a mountain in Bolivia, located near El Alto and about 25 km north of La Paz in the Cordillera Real.

Huayna Potosí is the closest high mountain to La Paz. Surrounded by high mountains, it is roughly 15 miles due north of the city, which makes this mountain the most popular climb in Bolivia. The normal ascent route is a fairly straightforward glacier climb, with some crevasses and a steep climb to the summit. However, the other side of the mountain—Huayna Potosí West Face—is the biggest face in Bolivia. Several difficult snow and ice routes ascend this 1,000-meter-high face.

The first ascent of the normal route was undertaken in 1919 by Germans Rudolf Dienst and Adolf Schulze. Some climbing books report this mountain as the “easiest 6,000er in the world”, but this claim is debatable. The easiest route entails an exposed ridge and sections of moderately steep ice, with a UIAA rating of PD. There are many 6,000 m mountains that are easier to climb in terms of technical difficulty. Perhaps therefore, the main reason Huayna Potosí has been referred to as the easiest 6,000 m climb is that the elevation gain from trailhead to summit is less than 1,400 m; with easy access from La Paz. Since La Paz is at 3,640 m, climbers have an easier time acclimatizing.

European climbing history of the mountain

In 1877 a group of six German climbers tried to climb Huayna Potosí for the first time. Without proper equipment and with little practical information, they set off toward the unclimbed peak. Their unsuccessful attempt met with tragedy. Four climbers died at an altitude around 5,600 m; the remaining two managed to retreat in deteriorating conditions, but died by exhaustion just after finding their way to the Zongo Pass. 21 years later, on 9 September 1898, an expedition of Austrian climbers attempted the mountain ascension again but after five days spent at 5,900 m they were forced to descend. Finally, in 1919 the Germans R. Dienst and O. Lhose reached the south summit (marginally higher than the north summit) climbing the mountain on the east face on a route that later would become the current normal route, with some variants.[5][6][7]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Huayna Potosí, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Vinicunca Panoramic

Daniel Sánchez Ibarra (Wikipedia)

![]()

Vinicunca, or Winikunka, also called Montaña de Siete Colores (literally: Mountain of seven colors), Montaña de Colores (Mountain of colors) or Montaña Arcoíris (Rainbow Mountain), is a mountain in the Andes of Peru with an altitude of 5,036 metres (16,522 ft) above sea level.[1][2] It is located on the road to the Ausangate mountain, in the Cusco region, between Cusipata District, province of Quispicanchi, and Pitumarca District, province of Canchis.[3]

Tourist access requires a two-hour drive from Cusco and a walk of about 5 kilometers (3.1 mi), or a three-and-a-half-hour drive through Pitumarca and a one-half-kilometre (0.31 mi) steep walk (1–1.5 hours) to the hill. As of 2019, no robust methods of transportation to Vinicunca have been developed to accommodate travelers, as it requires passage through a valley.[4]

In mid-2010, mass tourism came, attracted by the mountain’s series of stripes of various colors[5] due to its mineralogical composition on the slopes and summits.[6] The mountain used to be covered by glacier caps, but these melted.

Location

Vinicunca is located to the southeast of the city of Cusco and can be reached from Cusco via two routes: Cusipata or Pitumarca. One route is through the Peruvian Sierra del Sur (PE-3s) in the direction of the town of Checacupe, and further to the town of Pitumarca, which is around two hours from the city of Cusco. From Pitumarca, travelers may go by foot, car or motorbike along a trail passing through several rural communities such as Ocefina, Japura and Hanchipacha, and reach the community of Pampa Chiri, where a 1.5-kilometer walk along the Vinincunca pass leads to the natural formation with stripes of colors that give the name Rainbow Mountain. An alternative route is via Cusipata; from there, travelers may walk for 3 km along the Chillihuani route along a bridle path to the Rainbow Mountain.[7][8]

The altitude of the mountain is around 5200 meters or over 16,500 feet, so time for acclimatizing to the high altitude may be necessary during the trek up to the summit.[9]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Vinicunca, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

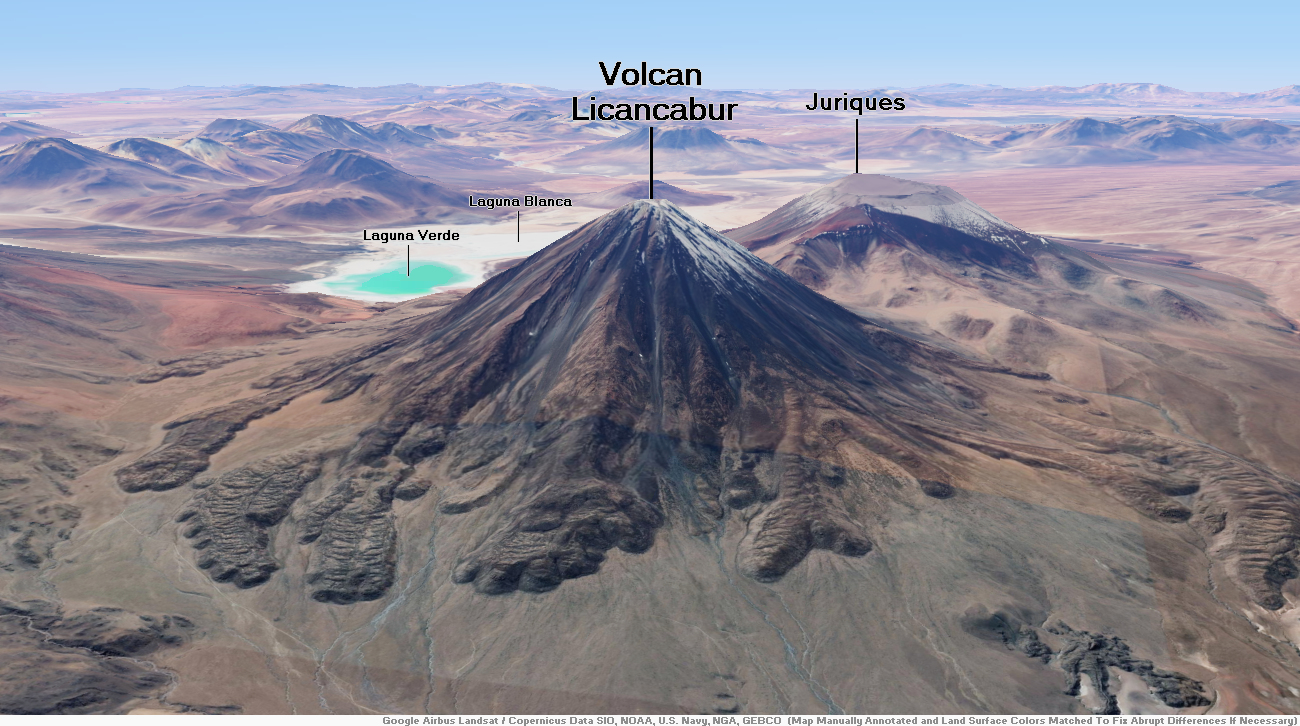

Huayna Picchu, Quechua: Wayna Pikchu, is a mountain in Peru around which the Urubamba River bends. It is located in the Cusco Region, Urubamba Province, Machupicchu District.[2] It rises over Machu Picchu, the so-called Lost City of the Incas. The Incas built a trail up the side of the Huayna Picchu and constructed temples and terraces at its top. The peak of Huayna Picchu is 2,693 metres (8,835 ft) above sea level, or about 260 metres (850 ft) higher than Machu Picchu.[3]

According to local guides, the top of the mountain was the residence for the high priest and the local virgins. Every morning before sunrise, the high priest with a small group would walk to Machu Picchu to signal the coming of the new day. The Temple of the Moon, one of the three major temples in the Machu Picchu area, is nestled on the side of the mountain and is situated at an elevation lower than Machu Picchu. Adjacent to the Temple of the Moon is the Great Cavern, another sacred temple with fine masonry. The other major local temples in Machu Picchu are the Temple of the Condor, Temple of Three Windows, Principal Temple, “Unfinished Temple”, and the Temple of the Sun, also called the Torreon.[4]

Its name is Hispanicized, possibly from the Quechua, alternative spelling Wayna Pikchu; wayna young, young man, pikchu pyramid, mountain or prominence with a broad base which ends in sharp peaks,[5][6] “young peak”. The current Quechua orthography used by the Ministerio de Cultura is Waynapicchu and Machupicchu.[7]

Tourism

Huayna Picchu may be visited throughout the year, but the number of daily visitors allowed on Huayna Picchu is restricted to 400. There are two times that visitors may enter the Huayna Picchu Trail; entrance between 7:00 and 8:00 AM and another from 10:00 to 11:00 AM. The 400 permitted hikers are split evenly between the two entrance times.

A steep and, at times, exposed pathway leads to the summit. Some portions are slippery and steel cables (a via ferrata) provide some support during the one-hour climb. The ascent is more challenging between November and April because the path up the mountain becomes slippery in the rainy season. Better climbing conditions can be expected during the dry season, which runs from May to September. There are two trails of varying lengths that visitors can take to hike to the summit. The shorter trail takes approximately 45–60 minutes to reach the top, while the longer trail takes approximately 3 hours to reach the summit.

From the summit, a second trail, which is currently closed for maintenance, leads down to the Gran Caverna and what is known as the Temple of the Moon.[8] These natural caves, on the northern face of the mountain, are lower than the starting point of the trail. The return path from the caves completes a loop around the mountain where it rejoins the main trail.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Huayna Picchu, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).