Map of Cascade Mountains

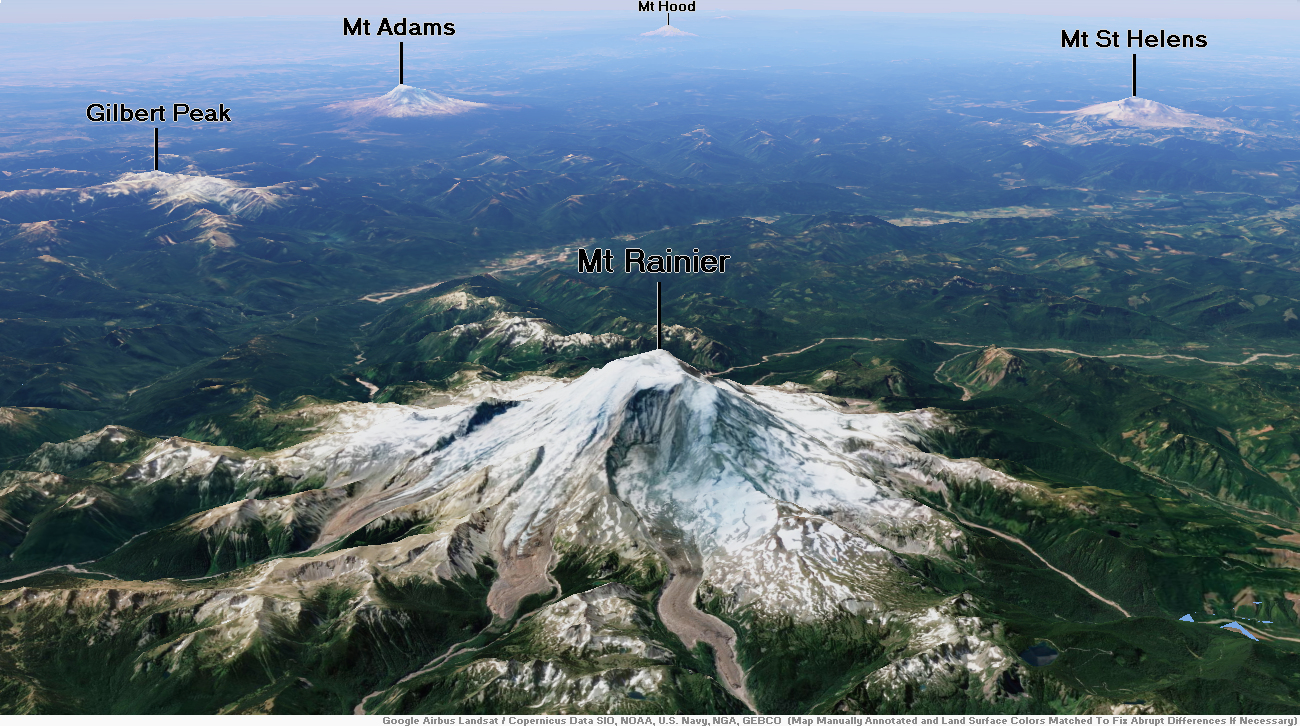

Mount Rainier Region

Mount Rainier Panoramic

Jerry S (Dreamstime)

Mount Rainier[a] (/reɪˈnɪər/ ray-NEER), also known as Tahoma, is a large active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest in the United States. The mountain is located in Mount Rainier National Park about 59 miles (95 km) south-southeast of Seattle.[9] With an officially recognized[b] summit elevation of 14,410 ft (4,392 m) at the Columbia Crest,[1][12] it is the highest mountain in the U.S. state of Washington, the most topographically prominent mountain in the contiguous United States,[2] and the tallest in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.

Due to its high probability of an eruption in the near future and proximity to a major urban area, Mount Rainier is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world, and it is on the Decade Volcano list.[13] The large amount of glacial ice means that Mount Rainier could produce massive lahars that could threaten the entire Puyallup River valley and other river valleys draining Mount Rainier, including the Carbon, White, Nisqually, and Cowlitz (above Riffe Lake).[14] According to the United States Geological Survey‘s 2008 report, “about 80,000 people and their homes are at risk in Mount Rainier’s lahar-hazard zones.”[15]

Between 1950 and 2018, 439,460 people climbed Mount Rainier.[16][17] Approximately 84 people died in mountaineering accidents on Mount Rainier from 1947 to 2018.[16]

Name

The many Indigenous peoples who have lived near Mount Rainier for millennia have many names for the mountain in their various languages. Lushootseed speakers have several names for Mount Rainier, including xʷaq̓ʷ and təqʷubəʔ.[c][5] xʷaq̓ʷ means “sky wiper” or “one who touches the sky” in English.[5] The word təqʷubəʔ means “snow-covered mountain”.[5][6] təqʷubəʔ has been anglicized in many ways, including ‘Tacoma’ and ‘Tacobet’.[18] Cowlitz speakers call the mountain təx̣ʷúma or təqʷúmen.[7] Sahaptin speakers call the mountain Tax̱úma, which is borrowed from Cowlitz.[8] Another anglicized name is Pooskaus.[19][clarification needed]

George Vancouver named Mount Rainier in honor of his friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier.[20] The map of the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804–1806 refers to it as “Mt. Regniere”. Although Rainier had been considered the official name of the mountain, Theodore Winthrop referred to the mountain as “Tacoma” in his posthumously published 1862 travel book The Canoe and the Saddle. For a time, both names were used interchangeably, although residents of the nearby city of Tacoma preferred Mount Tacoma.[21][22]

In 1890, the United States Board on Geographic Names declared that the mountain would be known as Rainier.[23] Following this in 1897, the Pacific Forest Reserve became the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve, and the national park was established three years later. Despite this, there was still a movement to change the mountain’s name to Tacoma and Congress was still considering a resolution to change the name as late as 1924.[24][25]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Rainier, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Mount Hood Panoramic

Chris Broyles

July 18, 2025 at 8:52 pm

Mount Hood, also known as Wy’east, is an active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range and is a member of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific Coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about 50 mi (80 km) east-southeast of Portland, on the border between Clackamas and Hood River counties, and forms part of the Mount Hood National Forest. Much of the mountain outside the ski areas is part of the Mount Hood Wilderness. With a summit elevation of 11,249 ft (3,429 m),[1] it is the highest mountain in the U.S. state of Oregon and is the fourth highest in the Cascade Range.[6] Ski areas on the mountain include Timberline Lodge ski area which offers the only year-round lift-served skiing in North America, Mount Hood Meadows, Mount Hood Skibowl, Summit Ski Area, and Cooper Spur ski area. Mt. Hood attracts an estimated 10,000 climbers a year.[7]

The peak is home to 12 named glaciers and snowfields. Mount Hood is considered the Oregon volcano most likely to erupt.[8] The odds of an eruption in the next 30 years are estimated at between 3 and 7%, so the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) characterizes it as “potentially active”, but the mountain is informally considered dormant.[9]

Establishments

Timberline Lodge is a National Historic Landmark located on the southern flank of Mount Hood just below Palmer Glacier, with an elevation of about 6,000 ft (1,800 m).[10]

The mountain has four ski areas: Timberline, Mount Hood Meadows, Ski Bowl, and Cooper Spur. They total over 4,600 acres (7.2 sq mi; 19 km2) of skiable terrain; Timberline, with one lift having a base at nearly 6,940 ft (2,120 m), offers the only year-round lift-served skiing in North America.[11]

There are a few remaining shelters on Mount Hood still in use today. Those include the Coopers Spur, Cairn Basin, and McNeil Point shelters as well as the Tilly Jane A-frame cabin. The summit was home to a fire lookout in the early 1900s; however, the lookout did not withstand the weather and no longer remains today.[12]

Mount Hood is within the Mount Hood National Forest, which comprises 1,067,043 acres (1,667 sq mi; 4,318 km2) of land, including four designated wilderness areas that total 314,078 acres (491 sq mi; 1,271 km2), and more than 1,200 mi (1,900 km) of hiking trails.[13][14]

The most northwestern pass around the mountain is called Lolo Pass. Native Americans crossed the pass while traveling between the Willamette Valley and Celilo Falls.[15]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Hood, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

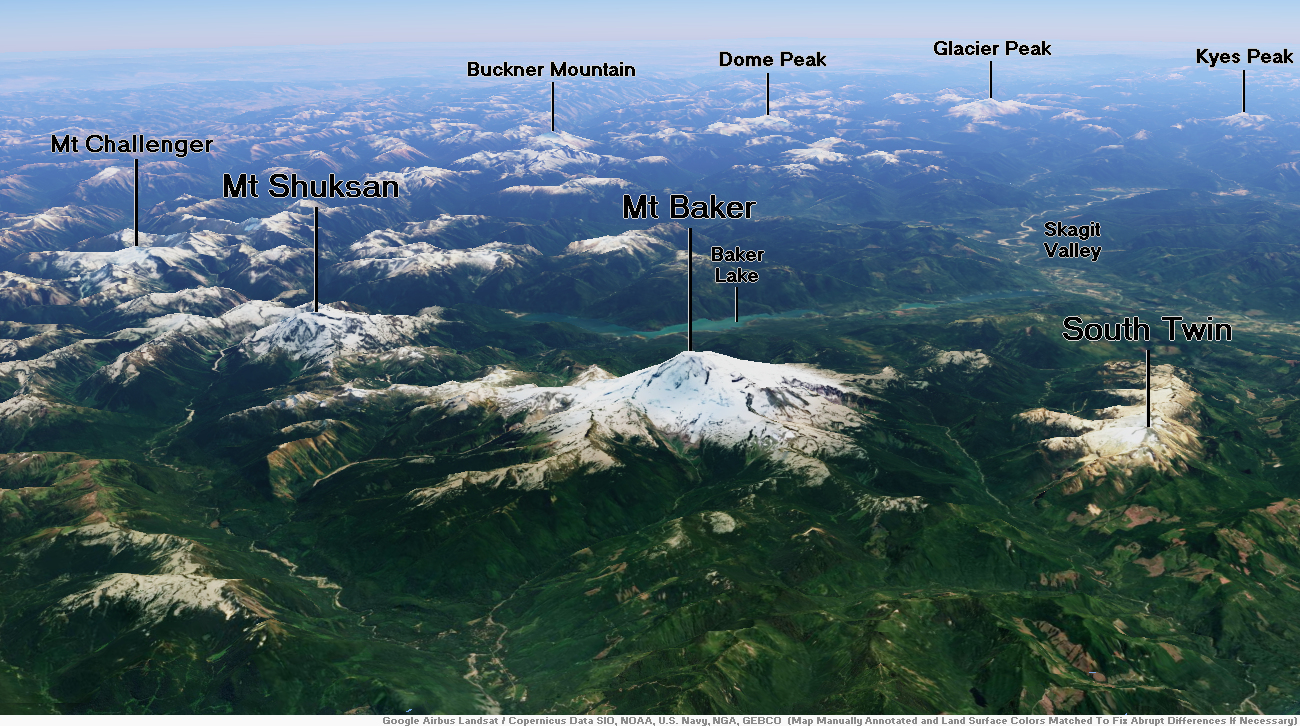

Map of North Cascades

Mount Shuksan Panoramic

Mount Shuksan is a glaciated massif[3] in the North Cascades National Park. Shuksan rises in Whatcom County, Washington immediately to the east of Mount Baker, and 11.6 miles (18.7 km) south of the Canada–US border. The mountain’s name Shuksan is derived from the Lummi word [šéqsən], said to mean “high peak”.[4] The highest point on the mountain is a three-sided peak known as Summit Pyramid.[5]

The mountain is composed of Shuksan greenschist, oceanic basalt that was metamorphosed when the Easton terrane collided with the west coast of North America, approximately 120 million years ago.[6] The mountain is an eroded remnant of a thrust plate formed by the Easton collision.[3]

The Mount Baker Highway, State Route 542, is kept open during the winter to support Mt. Baker Ski Area. In late summer, the road to Artist Point allows visitors to travel a few miles higher for a closer view of the peak. Picture Lake is accessible on the highway and reflects the mountain, making it a popular site for photography.

Sulphide Creek Falls, one of the tallest waterfalls in North America, plunges off the southeastern flank of Mount Shuksan. There are four other tall waterfalls that spill off Mount Shuksan and neighboring Jagged Ridge and Seahpo Peak, mostly sourced from small snowfields and glaciers.

The traditional name of Mount Shuksan in the Nooksack language is Shéqsan (“high foot”) or Ch’ésqen (“golden eagle”).[7] Both the Nooksack and Lummi are indigenous tribes who have occupied the watersheds of the Nooksack Rivers and Lummi River, respectively. They are both federally recognized tribes in the United States.

The first ascent of Mount Shuksan is usually attributed to Asahel Curtis and W. Montelius Price on September 7, 1906. However, in a 1907 letter to the editor of the Mazamas club journal, C. E. Rusk attributed the first ascent to Joseph Morowits in 1897. He said that he himself would have attempted it in 1903 if he had not been sure that it had already been climbed.[8]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Shuksan, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

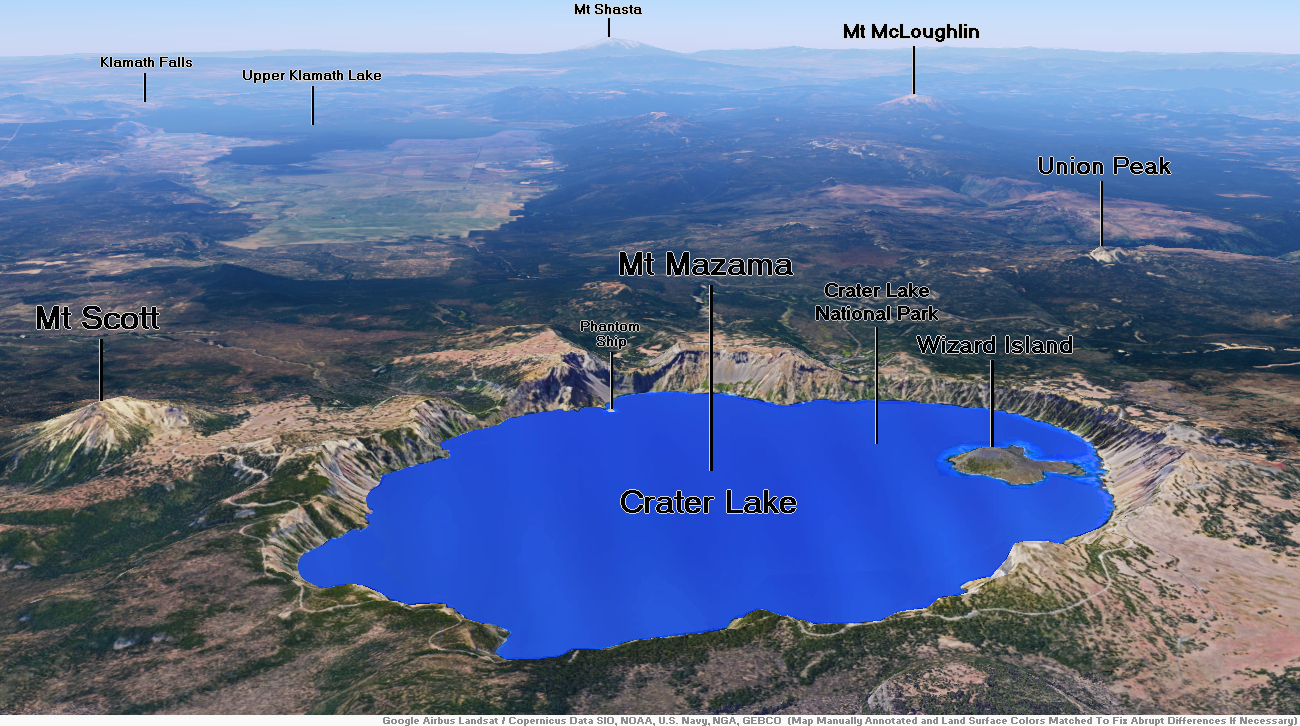

Map of Mount Mazama Region

Mount Mazama Panoramic (Crater Lake)

Achmathur (Wikipedia)

Mount Mazama (Klamath: Tum-sum-ne[5]) is a complex volcano in the western U.S. state of Oregon, in a segment of the Cascade Volcanic Arc and Cascade Range. The volcano is in Klamath County, in the southern Cascades, 60 miles (97 km) north of the Oregon–California border. Its collapse, due to the eruption of magma emptying the underlying magma chamber, formed a caldera that holds Crater Lake (Giiwas in the Native American language Klamath).[3] Mount Mazama originally had an elevation of 12,000 feet (3,700 m), but following its climactic eruption this was reduced to 8,157 feet (2,486 m). Crater Lake is 1,943 feet (592 m) deep, the deepest freshwater body in the U.S. and the second deepest in North America after Great Slave Lake in Canada.

Mount Mazama formed as a group of overlapping volcanic edifices such as shield volcanoes and small composite cones, becoming active intermittently until its climactic eruption 7,700 years ago. This eruption, the largest known within the Cascade Volcanic Arc in a million years, destroyed Mazama’s summit, reducing its approximate 12,000-foot (3,700 m) height by about 1 mile (1,600 m). Much of the edifice fell into the volcano’s partially emptied neck and magma chamber, creating a caldera. The region’s volcanic activity results from the subduction of the offshore oceanic plate, and is influenced by local extensional faulting. Mazama is dormant, but the U.S. Geological Survey says eruptions on a smaller scale are likely, which would pose a threat to its surroundings.

Native Americans have inhabited the area around Mazama and Crater Lake for at least 10,000 years and the volcano plays an important role in local folklore. European-American settlers first reached the region in the mid-19th century. Since the late 19th century, the area has been extensively studied by scientists for its geological phenomena and more recently for its potential sources of geothermal energy. Crater Lake and Mazama’s remnants sustain diverse ecosystems, which are closely monitored by the National Park Service because of their remoteness and ecological importance. Recreational activities including hiking, biking, snowshoeing, fishing, as well as cross-country skiing are available; during the summer, campgrounds and lodges at Crater Lake are open to visitors.

Geography

Mount Mazama is in Klamath County, within the U.S. state of Oregon,[2] 60 miles (97 km) north of the border with California. It lies in the southern portion of the Cascade Range. Crater Lake sits partly inside the volcano’s caldera,[6] with a depth of 1,943 feet (592 m);[note 1] it is the deepest body of freshwater in the United States[7][8] and the second deepest in North America after Great Slave Lake in Canada.[11] Before its caldera-forming eruption, Mazama stood at an elevation between 10,800 and 12,100 feet (3,300 and 3,700 m),[12] placing it about 1 mile (1.6 km) above the lake;[7] this would have made it Oregon’s highest peak.[9] The Global Volcanism Program currently lists its elevation at 8,157 feet (2,486 m).[1]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Mazma, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Mount Shasta Panoramic

Brian Graves

Mount Shasta (/ˈʃæstə/ SHASS-tə; Shasta: Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki;[5] Karuk: Úytaahkoo)[6] is a potentially active[7] stratovolcano at the southern end of the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California. At an elevation of 14,179 ft (4,322 m), it is the second-highest peak in the Cascades and the fifth-highest in the state. Mount Shasta has an estimated volume of 85 cubic miles (350 cubic kilometers), which makes it the most voluminous volcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.[8][9] The mountain and surrounding area are part of the Shasta–Trinity National Forest.

Description

The origin of the name “Shasta” is vague, either derived from a people of a name like it or otherwise garbled by early Westerners. Mount Shasta is connected to its satellite cone of Shastina, and together they dominate the landscape. Shasta rises abruptly to tower nearly 10,000 feet (3,000 m) above its surroundings.[4] On a clear winter day, the mountain can be seen from the floor of the Central Valley 140 miles (230 km) to the south.[10] The mountain has attracted the attention of poets,[11] authors,[12] and presidents.[13]

The mountain consists of four overlapping dormant volcanic cones that have built a complex shape, including the main summit and the prominent and visibly conical satellite cone of 12,330 ft (3,760 m) Shastina. If Shastina were a separate mountain, it would rank as the fourth-highest peak of the Cascade Range (after Mount Rainier, Rainier’s Liberty Cap, and Mount Shasta itself).[4]

Mount Shasta’s surface is relatively free of deep glacial erosion except, paradoxically, for its south side where Sargents Ridge[14] runs parallel to the U-shaped Avalanche Gulch. This is the largest glacial valley on the volcano, although it does not now have a glacier in it. There are seven named glaciers on Mount Shasta, with the four largest (Whitney, Bolam, Hotlum, and Wintun) radiating down from high on the main summit cone to below 10,000 ft (3,000 m) primarily on the north and east sides.[4] The Whitney Glacier is the longest, and the Hotlum is the most voluminous glacier in the state of California. Three of the smaller named glaciers occupy cirques near and above 11,000 ft (3,400 m) on the south and southeast sides, including the Watkins, Konwakiton, and Mud Creek glaciers.[citation needed]

History

The oldest-known human settlement in the area dates to about 7,000 years ago.[citation needed] At the time of Euro-American contact in the 1810s, the Native American tribes who lived within view of Mount Shasta included the Shasta, Okwanuchu, Modoc, Achomawi, Atsugewi, Karuk, Klamath, Wintu, and Yana tribes.

A historic eruption of Mount Shasta in 1786 may have been observed by Lapérouse, but this is disputed. Smithsonian Institution‘s Global Volcanism Program says that the 1786 eruption is discredited, and that the last known eruption of Mount Shasta was around 1250 AD, proved by uncorrected radiocarbon dating.[15][16]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Shasta, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

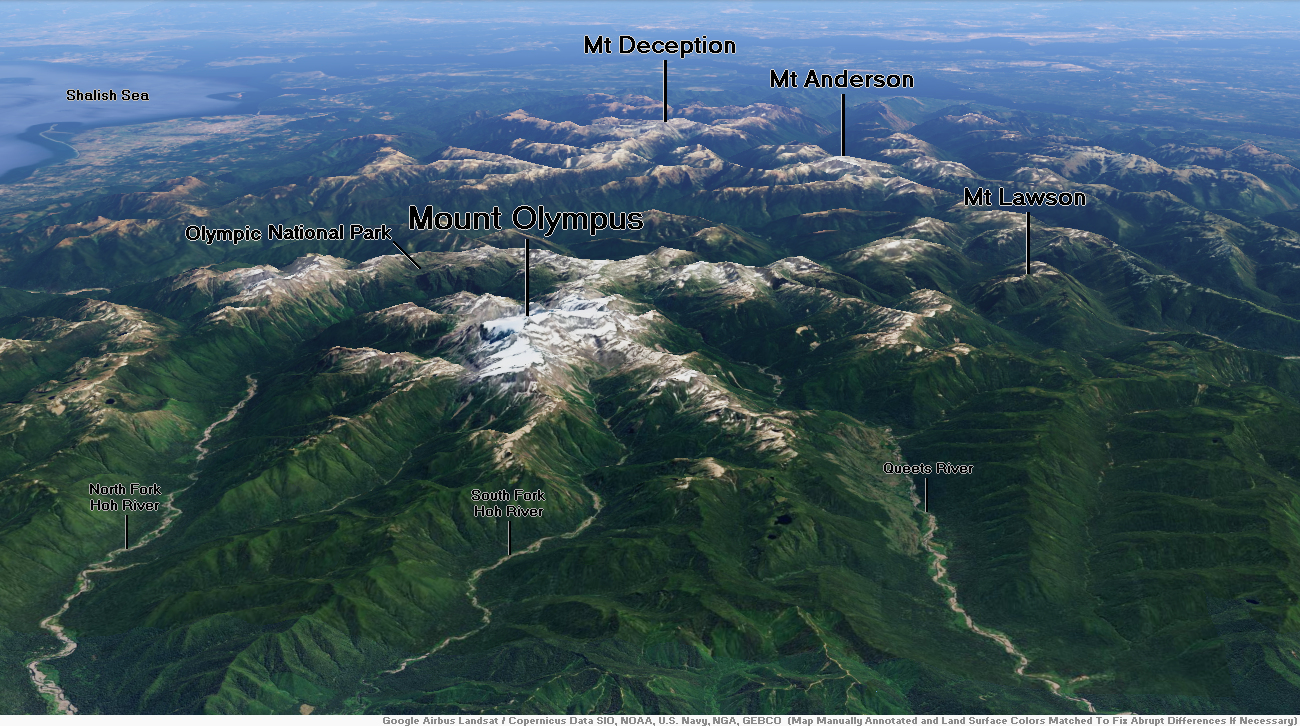

Mount Olympus Region

Mount Olympus Panoramic

Jeff Kish

![]()

Mount Olympus, at 7,980 feet (2,430 m), is the tallest and most prominent mountain in the Olympic Mountains of the U.S. state of Washington. Located on the Olympic Peninsula, it is also a central feature of Olympic National Park. Mount Olympus is the highest summit of the Olympic Mountains; however, peaks such as Mount Constance and The Brothers, on the eastern margin of the range, are better known, being visible from the Seattle metropolitan area.

Description

With notable local relief, Mount Olympus ascends over 2,100 m (6,900 ft) from the 293 m (961 ft) elevation confluence of the Hoh River with Glacier Creek in only 8.8 km (5.5 mi). Mount Olympus has 2,386 m (7,828 ft) of prominence, ranking 5th in the state of Washington.[5]

Due to heavy winter snowfalls, Mount Olympus supports large glaciers, despite its modest elevation and relatively low latitude. These glaciers include Blue, Hoh, Humes, Jeffers, Hubert, Black Glacier, and White, the longest of which is the Hoh Glacier at 3.06 miles (4.93 km). The largest is Blue with a volume of 0.14 cubic miles (0.57 km3) and area of 2.05 square miles (5.31 km2).[6] As with most temperate latitude glaciers,[7] these have all been shrinking in area and volume, and shortening in recent decades.

History

According to Edmond S. Meany (1923), Origin of Washington geographic names, citing Joseph A. Costello (1895), The Siwash, their life, legends and tales, the Duwamish used the name Sunh-a-do for the Olympian Mountains (or Coast Range in Costello 1895);[8][9] besides its unclear origin,[10] some references misuse this name for the Native American name of the mountain.[11] Spanish explorer Juan Pérez named the mountain Cerro Nevado de Santa Rosalía (“Snowy Peak of Saint Rosalia“) in 1774. This is said to be the first time a European named a geographic feature in what is now Washington state. On July 4, 1788, British explorer John Meares gave the mountain its present name.[12]

In 1890 an expedition, led by US Army officer Joseph P. O’Neil, reached the summit, of what is today presumed to have been the southern peak.[13]

On March 2, 1909, Mount Olympus National Monument was proclaimed by President Theodore Roosevelt.[14] On June 28, 1938, it was designated a national park by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[15] In 1976 the Olympic National Park became an International Biosphere Reserve. In 1981 it was designated a World Heritage Site.[16] In 1988 Congress designated 95% of the park as the Olympic Wilderness.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mount Olympus (Washington), which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).