Map of Alps

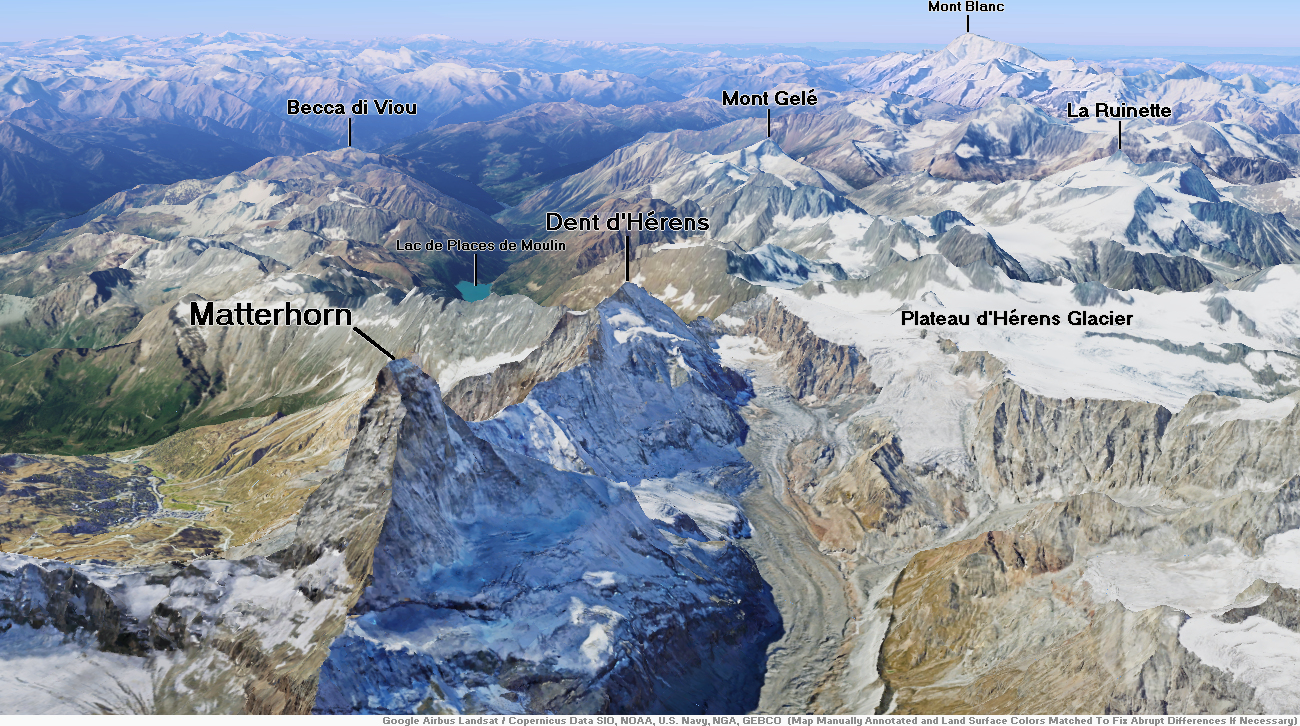

Matterhorn Region

Matterhorn Panoramic 1

Chris Broyles

June 22, 2024 at 11:46 am

“The Matterhorn Revealed” – Time-Lapse In Reverse – 15 Min Compressed Into 30 Sec

Matterhorn Panoramic 2

Sam Ferrara (Wikipedia)

The Matterhorn (German: [ˈmatɐˌhɔʁn] ⓘ, Swiss Standard German: [ˈmatərˌhɔrn]; Italian: Cervino [tʃerˈviːno]; French: Cervin [sɛʁvɛ̃]; Romansh: Mont(e) Cervin(u)[note 3] or Matterhorn [mɐˈtɛrorn]) is a mountain of the Alps, straddling the main watershed and border between Italy and Switzerland. It is a large, near-symmetric pyramidal peak in the extended Monte Rosa area of the Pennine Alps, whose summit is 4,478 metres (14,692 ft) above sea level, making it one of the highest summits in the Alps and Europe.[note 4] The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points and are split by the Hörnli, Furggen, Leone/Lion, and Zmutt ridges. The mountain overlooks the Swiss town of Zermatt, in the canton of Valais, to the northeast; and the Italian town of Breuil-Cervinia in the Aosta Valley to the south. Just east of the Matterhorn is Theodul Pass, the main passage between the two valleys on its north and south sides, which has been a trade route since the Roman Era.

The Matterhorn was studied by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in the late eighteenth century, and was followed by other renowned naturalists and artists, such as John Ruskin, in the 19th century. It remained unclimbed after most of the other great Alpine peaks had been attained and became the subject of an international competition for the summit. The first ascent of the Matterhorn was in 1865 from Zermatt by a party led by Edward Whymper, but during the descent, a sudden fall claimed the lives of four of the seven climbers. This disaster, later portrayed in several films, marked the end of the golden age of alpinism.[3] The north face was not climbed until 1931 and is among the three biggest north faces of the Alps, known as “The Trilogy”. The west face, the highest of the Matterhorn’s four faces, was completely climbed only in 1962. It is estimated that over 500 alpinists have died on the Matterhorn, making it one of the deadliest peaks in the world.[4]

The Matterhorn is mainly composed of gneisses (originally fragments of the African Plate before the Alpine orogeny) from the Dent Blanche nappe, lying over ophiolites and sedimentary rocks of the Penninic nappes. The mountain’s current shape is the result of cirque erosion due to multiple glaciers diverging from the peak, such as the Matterhorn Glacier at the base of the north face. Sometimes referred to as the Mountain of Mountains (German: Berg der Berge),[5] it has become an indelible emblem of the Alps in general. Since the end of the 19th century, when railways were built in the area, the mountain has attracted increasing numbers of visitors and climbers. Each year, numerous mountaineers try to climb the Matterhorn from the Hörnli Hut via the northeast Hörnli ridge, the most popular route to the summit. Many trekkers also undertake the 10-day-long circuit around the mountain. The Matterhorn has been part of the Swiss Federal Inventory of Natural Monuments since 1983.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Matterhorn, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Additional Matterhorn Images Are Here

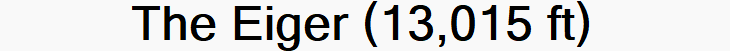

The Eiger Panoramic 1

Murray Foubister (Wikipedia)

The Eiger Panoramic 2

Gabrielle Merk (Wikipedia)

![]()

The Eiger (German pronunciation: [ˈaɪ̯ɡɐ] ⓘ) is a 3,967-metre (13,015 ft) mountain of the Bernese Alps, overlooking Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen in the Bernese Oberland of Switzerland, just north of the main watershed and border with Valais. It is the easternmost peak of a ridge crest that extends across the Mönch to the Jungfrau at 4,158 m (13,642 ft), constituting one of the most emblematic sights of the Swiss Alps. While the northern side of the mountain rises more than 3,000 m (10,000 ft) above the two valleys of Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen, the southern side faces the large glaciers of the Jungfrau-Aletsch area, the most glaciated region in the Alps. The most notable feature of the Eiger is its nearly 1,800-metre-high (5,900 ft) north face of rock and ice, named Eiger-Nordwand, Eigerwand or just Nordwand, which is the biggest north face in the Alps.[3] This substantial face towers over the resort of Kleine Scheidegg at its base, on the eponymous pass connecting the two valleys.

The first ascent of the Eiger was made by Swiss guides Christian Almer and Peter Bohren and Irishman Charles Barrington, who climbed the west flank on August 11, 1858. The north face, the “last problem” of the Alps, considered amongst the most challenging and dangerous ascents, was first climbed in 1938 by an Austrian-German expedition.[4] The Eiger has been highly publicized for the many tragedies involving climbing expeditions. Since 1935, at least 64 climbers have died attempting the north face, earning it the German nickname Mordwand, literally “murder(ous) wall”—a pun on its correct title of Nordwand (North Wall).[5]

Although the summit of the Eiger can be reached by experienced climbers only, a railway tunnel runs inside the mountain, and two internal stations provide easy access to viewing-windows carved into the rock face. They are both part of the Jungfrau Railway line, running from Kleine Scheidegg to the Jungfraujoch, between the Mönch and the Jungfrau, at the highest railway station in Europe. The two stations within the Eiger are Eigerwand (behind the north face) and Eismeer (behind the south face), at around 3,000 metres. The Eigerwand station has not been regularly served since 2016.

Etymology

The first mention of Eiger, appearing as “mons Egere”, was found in a property sale document of 1252, but there is no clear indication of how exactly the peak gained its name.[6] The three mountains of the ridge are commonly referred to as the Virgin (German: Jungfrau – translates to “virgin” or “maiden”), the Monk (Mönch), and the Ogre (Eiger; the standard German word for ogre is Oger). The name has been linked to the Latin term acer, meaning “sharp” or “pointed”.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Eiger, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Mont Blanc Region

Mont Blanc Panoramic

Murray Foubister (Wikipedia)

![]()

Mont Blanc (BrE: /ˌmɒ̃ˈblɒ̃(k)/; AmE: /ˌmɒn(t)ˈblɑːŋk/)[a] is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, and the highest mountain in Europe outside the Caucasus Mountains, rising 4,805.59 m (15,766 ft)[1] above sea level, located on the Franco-Italian border.[3] It is the second-most prominent mountain in Europe, after Mount Elbrus, and the 11th most prominent mountain in the world.[4]

It gives its name to the Mont Blanc massif, which straddles parts of France, Italy and Switzerland. Mont Blanc’s summit lies on the watershed line between the valleys of Ferret and Veny in Italy, and the valleys of Montjoie, and Arve in France. Ownership of the summit area has long been disputed between France and Italy.

The Mont Blanc massif is popular for outdoor activities like hiking, climbing, trail running and winter sports like skiing, and snowboarding. The most popular climbing route to the summit of Mont Blanc is the Goûter Route, which typically takes two days.

The three towns and their communes which surround Mont Blanc are Courmayeur in Aosta Valley, Italy; and Saint-Gervais-les-Bains and Chamonix in Haute-Savoie, France. The latter town was the site of the first Winter Olympics. A cable car ascends and crosses the mountain range from Courmayeur to Chamonix through the Col du Géant. The 11.6 km (7+1⁄4 mi) Mont Blanc Tunnel, constructed between 1957 and 1965, runs beneath the mountain and is a major transalpine transport route.

Geology

Mont Blanc and adjacent mountains in the massif are predominately formed from a large intrusion of granite (termed a batholith) which was forced up through a basement layer of gneiss and mica schists during the Variscan mountain-forming event of the late Palaeozoic period. The summit of Mont Blanc is located at the point of contact of these two rock types. To the southwest, the granite contact is of a more intrusive nature, whereas to the northeast it changes to being more tectonic. The granites are mostly very-coarse grained, ranging in type from microgranites to porphyroid granites. The massif is tilted in a north-westerly direction and was cut by near-vertical recurrent faults lying in a north–south direction during the Variscan orogeny. Further faulting with shear zones subsequently occurred during the later Alpine orogeny. Repeated tectonic phases have caused breakup of the rock in multiple directions and in overlapping planes. Finally, past and current glaciation caused significant sculpting of the landscape into its present-day form.[5]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Mont Blanc, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

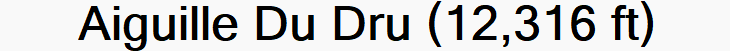

The Aiguille du Dru (also the Dru or the Drus; French, Les Drus) is a mountain in the Mont Blanc massif in the French Alps. It is situated to the east of the village of Les Praz in the Chamonix valley. “Aiguille” means “needle” in French.

The mountain’s highest summit is:

- Grande Aiguille du Dru (or the Grand Dru) 3,754 m

Another, slightly lower sub-summit is:

- Petite Aiguille du Dru (or the Petit Dru) 3,733 m.

The two summits are on the west ridge of the Aiguille Verte (4,122 m) and are connected to each other by the Brèche du Dru (3,697 m). The north face of the Petit Dru is considered one of the six great north faces of the Alps.

The southwest “Bonatti Pillar” and its eponymous climbing route were destroyed in a 2005 rock fall.[2][3]

Ascents

The first ascent of the Grand Dru was by British alpinists Clinton Thomas Dent and James Walker Hartley, with guides Alexander Burgener and K. Maurer, who climbed it via the south-east face on 12 September 1878. Dent, in his description of the climb, wrote:

Those who follow us, and I think there will be many, will perhaps be glad of a few hints about this peak. Taken together, it affords the most continuously interesting rock climb with which I am acquainted. There is no wearisome tramp over moraine, no great extent of snow fields to traverse. Sleeping out as we did, it would be possible to ascend and return to Chamonix in about 16 to 18 hrs. But the mountain is never safe when snow is on the rocks, and at such times stones fall freely down the couloir leading up from the head of the glacier. The best time for the expedition would be, in ordinary seasons, in the month of August. The rocks are sound and are peculiarly unlike those of other mountains. From the moment the glacier is left, hard climbing begins, and the hands as well as the feet are continuously employed. The difficulties are therefore enormously increased if the rocks be glazed or cold; and in bad weather the crags of the Dru would be as pretty a place for an accident as can well be imagined.[4]

The Petit Dru was climbed in the following year, on 29 August 1879, by J. E. Charlet-Straton, P. Payot and F. Follignet via the south face and the south-west ridge. The first traverse of both summits of the Drus was by E. Fontaine and J. Ravanel on 23 August 1901. The first winter traverse of the Drus was by Armand Charlet and Camille Devouassoux on 25 February 1938.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Aiguille du Dru, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

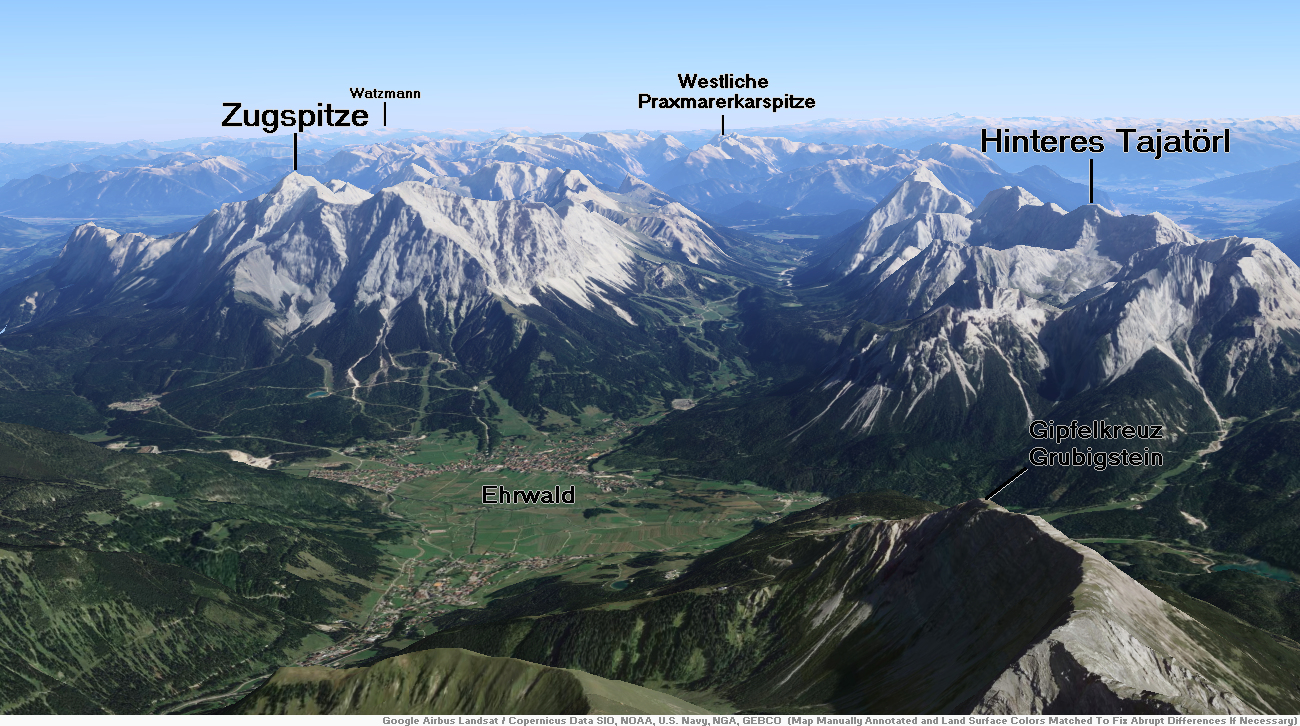

Zugspitze Region

Zugspitze Panoramic

Wirestock (Freepik)

![]()

The Zugspitze (/ˈzʊɡʃpɪtsə/ ZUUG-shpit-sə,[4] German: [ˈtsuːkˌʃpɪtsə] ⓘ; lit. '[avalanche] path peak’), at 2,962 m (9,718 ft) above sea level, is the highest peak of the Wetterstein Mountains and the highest mountain in Germany. It lies south of the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Bavaria, and the Austria–Germany border is on its western summit. South of the mountain is the Zugspitzplatt, a high karst plateau with numerous caves. On the flanks of the Zugspitze are two glaciers, the largest in Germany: the Northern Schneeferner with an area of 30.7 hectares and Höllentalferner with an area of 24.7 hectares. Shrinking of the Southern Schneeferner led to the loss of glacier status in 2022.[5]

The Zugspitze was first climbed on 27 August 1820 by Josef Naus; his survey assistant, Maier, and mountain guide, Johann Georg Tauschl. Today there are three normal routes to the summit: one from the Höllental valley to the northeast; another out of the Reintal valley to the southeast; and the third from the west over the Austrian Cirque (Österreichische Schneekar). One of the best known ridge routes in the Eastern Alps runs along the knife-edged Jubilee Ridge (Jubiläumsgrat) to the summit, linking the Zugspitze, the Hochblassen and the Alpspitze. For mountaineers there is plenty of nearby accommodation. On the western summit of the Zugspitze itself is the Münchner Haus and on the western slopes is the Wiener-Neustädter Hut.

Three cable cars run to the top of the Zugspitze. The first, the Tyrolean Zugspitze Cable Car, was built in 1926 by the German company Adolf Bleichert & Co[6] and terminated on an arête below the summit at 2,805 m.a.s.l, the so-called Kammstation, before the terminus was moved to the actual summit at 2,951 m.a.s.l. in 1991. A rack railway, the Bavarian Zugspitze Railway, runs inside the northern flank of the mountain and ends on the Zugspitzplatt, from where a second cable car runs a short way down to the Schneefernerhaus, formerly a hotel, but since 1999 an environmental research station; a weather station opened there in 1900. The rack railway and the Eibsee Cable Car, the third cableway, transport an average of 500,000 people to the summit each year. In winter, nine ski lifts cover the ski area on the Zugspitzplatt.

Geography

The Zugspitze belongs to the Wetterstein range of the Northern Limestone Alps. The Austria–Germany border goes right over the mountain. There used to be a border checkpoint at the summit but, since Germany and Austria are now both part of the Schengen zone, the border crossing is no longer staffed.

The exact height of the Zugspitze was a matter of debate for quite a while. Given figures ranged from 2,690–2,970 metres (8,830–9,740 ft), but it is now generally accepted that the peak is 2,962 m (9,718 ft) above sea level as a result of a survey carried out by the Bavarian State Survey Office. The lounge at the new café is named “2962” for this reason.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Zugspitze, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

Watzmann Panoramic

Smileus (iStock)

![]()

The Watzmann (Bavarian: Watzmo) is a mountain in the Berchtesgaden Alps south of the village of Berchtesgaden. It is the third highest in Germany, and the highest located entirely on German territory.[1]

Three main peaks array on a N-S axis along a ridge on the mountain’s taller western half: Hocheck (2,651 m), Mittelspitze (Middle Peak, 2,713 m) and Südspitze (South Peak, 2,712 m).

The Watzmann massif also includes the 2,307 m Watzmannfrau (Watzmann Wife, also known as Kleiner Watzmann or Small Watzmann), and the Watzmannkinder (Watzmann Children), five lower peaks in the recess between the main peaks and the Watzmannfrau.

The entire massif lies inside Berchtesgaden National Park.

Watzmann Glacier and other icefields

The Watzmann Glacier is located below the famous east face of the Watzmann in the Watzmann cirque and is surrounded by the Watzmanngrat arête, the Watzmannkindern and the Kleiner Watzmann.

The size of the glacier reduced from around 30 hectares (74 acres) in 1820 until it split into a few fields of firn, but between 1965 and 1980 it advanced significantly again[2] and now has an area of 10.1 hectares (25 acres).[3]

Above and to the west of the icefield lie the remains of a JU 52 transport-bomber that crashed in October 1940.

Amongst the other permanent snow and icefields the Eiskapelle (“Ice Chapel”) is the best known due to its easy accessibility from St. Bartholomä. The Eiskapelle may well be the lowest lying permanent snowfield in the Alps. Its lower end is only 930 metres high in the upper Eisbach valley and is about an hour’s walk from St. Bartholomä on the Königssee. The Eiskapelle is fed by mighty avalanches that slide down from the east face of the Watzmann in spring and accumulate in the angle of the rock face. Sometimes a gate-shaped vault forms in the ice at the point where the Eisbach emerges from the Eiskapelle. Before entering there is an urgent warning sign that others have been killed by falling ice.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Watzmann, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

Triglav (pronounced [ˈtɾiːɡlau̯]; German: Terglau; Italian: Tricorno), with an elevation of 2,863.65 metres (9,395 ft 2+1⁄8 in),[1][notes 1] is the highest mountain in Slovenia and the highest peak of the Julian Alps. The mountain is the pre-eminent symbol of the Slovene nation, appearing on the coat of arms and flag of Slovenia. It is the centrepiece of Triglav National Park, Slovenia’s only national park. Triglav was also the highest peak in Yugoslavia before Slovenia’s independence in 1991.

Name

Various names have been used for the mountain through history. An old map from 1567 used the Latin name Ocra mons, whereas Johann Weikhard von Valvasor called it Krma (the modern name of an Alpine valley in the vicinity) in the second half of the 17th century.[3] According to the German mountaineer and professor Adolf Gstirner, the name Triglav first appeared in written sources as Terglau in 1452, but the original source has been lost.[4] The next known occurrence of Terglau is cited by Gstirner and is from a court description of the border in 1573.[5] Early forms of the name Triglav also include Terglau in 1612, Terglou in 1664 and Terklou around 1778–1789. The name is derived from the compound *Tri-golvъ (literally ‘three-head’—that is, ‘three peaks’), which may be understood literally because the mountain has three peaks when viewed from much of Upper Carniola. It is unlikely that the name has any connection to the Slavic deity Triglav.[6] In the local dialect, the name is pronounced [tərˈgwɔu̯] (with a second-syllable accent, as if it was written Trglov, with the dark L experiencing vocalization) in contrast to standard Slovene Tríglav.[7] The highest peak is sometimes also called Big Mount Triglav (Slovene: Veliki Triglav)[8] to distinguish it from Little Mount Triglav[9] (Mali Triglav, 2,738 meters or 8,983 feet) immediately to the east.

History

The first recorded ascent of Triglav was achieved in 1778, at the initiative of the industrialist and polymath Sigmund Zois.[10] According to the most commonly cited report, published in the newspaper Illyrisches Blatt in 1821 by the historian and geographer Johann Richter, these were the surgeon Lovrenz Willomitzer (written as Willonitzer by Richter), the chamois hunter Štefan Rožič, and the miners Luka Korošec and Matevž Kos. According to a report by Belsazar Hacquet in his Oryctographia Carniolica, the ascent took place towards the end of 1778, by two chamois hunters, one of them being Luka Korošec, and one of his former students, whose name is not mentioned.[11]

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Triglav, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

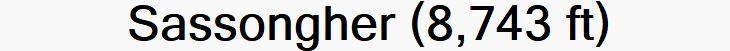

Sass Rigais Region

![]()

Sas Rigais (3,025 m) is a mountain of the northwestern Dolomites in South Tyrol, northern Italy. Along with the nearby Furchetta, which is exactly the same height and only 600m away, it is the highest peak of the Geisler group. Sas Rigais offers hikers one of few Dolomites’ three-thousanders the entire crossing from one side of the mountain to the other. The Via ferrata Villnössersteig is categorized between a B and C difficulty and the trail Sass Rigais steig is rated C. A crucifix is located at the summit.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Sass Rigais, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

The Seceda (Sec?da in Ladin) is a mountain at the foot of the Odle group, located in Val Gardena, above the town of Ortisei. Its summit can be reached by a cable car from the town center.

From the top of the Seceda, since 1997, the ski race S?dtirol Gardenissima starts.

Ascent to the summit

The easiest way to reach the peak of the Seceda (2518 meters above sea level) is through the ski lift that starts from Ortisei and directly reaches the top with its panoramic point, or through the ski lift that starts from Santa Cristina Valgardena and reaches the Col Raiser (2107 meters above sea level). Whether you arrive with the Seceda cable car or the Col Raiser cable car, there are numerous shelters and restaurants that can be used as a foothold and refreshment.

The summit, however, can also be reached on foot from the south from Ortisei, Santa Cristina or from Selva di Val Gardena or from the north from the municipality of Funes. Starting from Selva you can follow the path 3 from Daunei to the refuge Florence and then continue towards the Pietralongia and finally climb to the top of Mount Seceda.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Seceda, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

The Sassongher is a mountain in the Dolomites of Gardena, 2,665 m. s.l.l., belonging to the Puez-Odle group, located within the Puez-Odle natural park: it dominates, with its imposing size, the villages of Corvara and Colfosco, in Alta Badia.

Mountaineering

Access

To get to the top of the Sassongher starting from Colfosco (fraction of Corvara) you can reach the Col Pradat refuge in the cable car (2,038 m above sea level) and then you reach the fork Sassongher. From here, with path no. 7, you reach a top at 2,665 meters above sea level. It is also possible to reach the summit from the Gardenaccia refuge (2,050 m a.s.l.) following the path n. 5 up to the fork Sassongher and then the n. 7, from Funtanacia for the Juèl val (path no. 7 up to the fork and then to the summit) or from the refuge Puez (2,475 m a.s.l.) with paths no. 2 and 15 until the Gardenacia pass and from here with no. 5 up to the fork Sassongher and n. 7 to the top.

Ascension

It is certain that for centuries farmers and hunters passed through the Sassongher moving from valley to valley. It is worth mentioning the climb of the south wall made by Joseph Kostner, alpine guide of Corvara, in August 1900.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Sassongher, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).

![]()

The Three Peaks of Lavaredo (Drei Zinnen in German ; Tré Zìmes in Ladin Cadore[[1]) are three peaks of the Dolomites site in the municipality of Auronzo di Cadore and bordering on that of the Dolomites of Sesto in the municipality of Dobbiaco; they are considered among the most famous mountains in the world of mountaineering, with the Cima Grande which represents one of the classic northern walls of the Alps, and allow the panoramic view of the mountains.

The lyonimo

The oldest attestations of the toponym refer to the German forms, so much so that the names Dreyspiz (literally “three tips”), dre? Spitz and Zwain hospin Spizenn have been found since the Cinquesixteenth and seventeenth [centuries.[2] In the famous “Atlas Tyrolensis” of 1774 by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber the peaks are referred to as 3 Zinnern Spize. However, evidence supporting the German origin of the toponym is rather sparse.[[3]

History

Between 1915 and 1917 the peaks of the Lavaredo were the war front. Of this period there are still evident remains (tres and tunnels, tunnels, barracks) on the massif and on the nearby Monte Paterno.

On 9 July 1974 a Bell 206 helicopter of the Italian Army (EI613) fell between the Three Peaks and Mount Paterno, piloted by Captain Pier Maria Medici of the Army Air Force. On board were also the two officers of the “Tridentina” Alpine Brigade Renzo Bulfone and Gianfranco Lastri.[[4] In memory of the accident, between the two mountains there is a memorial plaque, also composed of the same blades of the helicopter.

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Tre Cime di Lavaredo, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International License (view authors).